We at The Children Of The Revolution believe that the future of authentic conservatism depends entirely on our ability to teach our beliefs in a rational and open manner. Indeed, we have seen first-hand the fruits of the coordinated indoctrination of the youth of this country by agenda-driven liberals as we ourselves passed through the public and higher education systems in America. Consequently, we understand how lopsided the knowledge that our generation has accrued through their education actually is, and further how arduous such an effort to educate them in the principles of conservatism will be. Nevertheless, we have committed ourselves that such a course is necessary to the survival and eventual re-emergence of what a fellow blogger has dubbed “rational conservatism,” but in essence is merely the continuation of the principles of our nation’s founding. To that end, we begin what will be a series of treatises aimed at Teaching Conservatism.

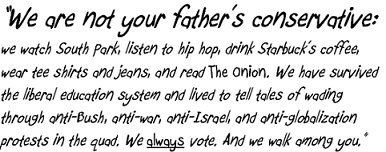

We at The Children Of The Revolution believe that the future of authentic conservatism depends entirely on our ability to teach our beliefs in a rational and open manner. Indeed, we have seen first-hand the fruits of the coordinated indoctrination of the youth of this country by agenda-driven liberals as we ourselves passed through the public and higher education systems in America. Consequently, we understand how lopsided the knowledge that our generation has accrued through their education actually is, and further how arduous such an effort to educate them in the principles of conservatism will be. Nevertheless, we have committed ourselves that such a course is necessary to the survival and eventual re-emergence of what a fellow blogger has dubbed “rational conservatism,” but in essence is merely the continuation of the principles of our nation’s founding. To that end, we begin what will be a series of treatises aimed at Teaching Conservatism.There are countless misconceptions about conservatism, primarily due to a co-opting of our message and name by political partisans on both sides of the aisle. It is assumed that a “conservative” is just another name for a “Republican.” It is further assumed that a conservative is a Warhawk and a religious fundamentalist. These perceptions are utter fallacy and are a result in part of the evolution of election strategies, designed to garner support from certain powerful voting blocks. True conservatives adhere to a set of core principles that are immutable, as they are a reflection of the inalienable rights recognized by our Declaration of Independence. Political parties, by comparison, are entities that change based upon shifting attitudes, polling data, and the events of history. Conservatives may tend to vote with one party more than another, but our allegiance is to our principles rather than primacy of any one party, person or special interest.

That having been said, there is a reason why conservatives have trended toward voting Republican in the past. Until recently, Republicans have postured themselves as the party of “small government.” The Democrat alternative was one of baldly stated federal government increases in spending and authority. While we may debate the Republican Party’s motives and certainly take due note of the fruits of their “small government” policies (namely, the increase in the size and power of the federal government to an all time high), the argument for limited government found a prominent voice with their party alone. That all, of course, has changed. Conservatives find themselves little satisfied, in fact in large part disgusted, by the excesses of both parties and shy like a battered dog from the Republican enticements of renewed commitment to small government policies.

But why do we conservatives advocate limited government? Sadly, the answer to that question is no longer obvious to many Americans. At its core, the conservative argument is founded upon a simple and logical precept, mathematical in nature. That principle is that the more decisions that government is permitted to make for you, the fewer decisions you are able to make for yourself. Essentially, two objects cannot occupy the same space. In a very real and not just rhetorical sense, expanded government, be it in spending and revenue collection or otherwise, is equivalent to a usurpation of your natural freedom. Typically in history this usurpation has occurred by force, with the government taking what it wanted regardless of the will of its citizens. In our American republic, however, we find ourselves, the citizens, in the unique situation of deciding whether to keep our freedoms or give more of them away to our government. This is, of course, a cost-benefit analysis for us. We are not induced by our government or politicians to relinquish freedoms unless there is some sort of payoff. An example (simplified) of this sort of tradeoff would be Universal Healthcare. Nowhere in the Constitution is there an enumerated right to government-furnished healthcare, however we are presented with the choice of affording that power to government in exchange for increased taxes and the intrusion of government into the healthcare industry, which would have an impact upon the free market. There are many citizens who view this tradeoff as fair and equitable. There are also many, namely conservatives, who do not view it as such.

The conservative maxim of limited government means that we typically will vote down or oppose any increase in the size or authority of federal government; and yes, that includes overburdensome taxes, which are an infringement upon your property. There are rare exceptions, but it is indeed fair to peg conservatives as “small government” people. This is the heart and soul of our movement. And where does this principle come from? As with nearly all conservative tenets, it is taken directly from the founding of our nation. While the Founders disagreed on a great deal, one thing they all agreed upon in drafting the Constitution was that the federal government should be limited in its powers. They did this by specifying the powers of the federal government in Articles I-VI (Article VII dealing with the ratification of the Constitution itself) and by including the Tenth Amendment to the Bill of Rights, which clearly devolves any powers not specified in those Articles to the states and the people themselves. Supreme Court Justice John Marshall made this plain in the case of McCulloch v. Maryland in 1819 by stating:

“This government is acknowledged by all, to be one of enumerated powers. The principle, that it can exercise only the powers granted to it, would seem too apparent, to have required to be enforced by all those arguments, which its enlightened friends, while it was depending before the people, found it necessary to urge; that principle is now universally admitted.”

Nevertheless, liberalism espouses a view that powers peripheral or related to those enumerated in the Constitution but not themselves specified should be granted to the federal government as well. This is in direct opposition to the conservative philosophy of originalism, which holds that the Constitution means exactly what it says and no more. This is a central source of conflict between conservatives and liberals and as such is at the heart of most hot-button political issues, particularly judicial appointments.

The reasoning behind the Founders’ collective decision to limit federal power is the simple truth that a single individual has a better notion of what is in his/her own interest than his/her government. Similarly, they reasoned that state and local government, composed of smaller units of citizens rather than the diverse nation as a whole, should be the focus of government for the people. In all cases, however, the idea was and is to constrain government as much as is practical in order to allow individuals to make more decisions for themselves, in the interest of their prosperity.

So what does limited government mean in a practical sense? First and foremost, it means that you are secure in your person and property. You are at liberty to retain more of your income, you are free from unreasonable search or seizure by the police, you are free to defend yourself and your home (with a firearm, if you so choose), you are free to pursue any path so long as it does not infringe upon the life and liberty of others. It also means sacrifices. Fewer social programs in the mold of social security, Medicare and welfare as they exist today. Accountability for your decisions, should they land you in poverty or jail. It means living with the reality of a federal government that refuses to solve your problems for you. Adherence to limited government also means, as most of the Founders agreed, limitation of warfare strictly to the defense of American property and the American nation, as executive power is at its greatest and most autocratic during times of war, particularly prolonged war of the sort the Founders observed in Europe.

In the articles that follow in the Teaching Conservatism series, we will deal with many specific issues and the conservative stance, however it is important to remember that at the heart of nearly every issue, the goal for conservatism is to constrain government power as much as is reasonably possible to uplift the individual American. When in political doubt, the conservative will ask him or herself: will this unduly expand government authority?

5 comments:

Beautifully articulated, as usual.

Well argued, and thanks for the link :-)

Really, I only take issue with your last statement. It should probably read: "will this expand federal government?". The 'unduly' tag is a slippery slope that, at least for this conservative, should never enter one's mind.

Otherwise well said, my contribution will be forthcoming.

I think liberals and conservatives agree that the government should

have little or no authority over "social issues" or to legislate

morality; this is one way we both differ from the religious right.

Neither want a surveillance or police state. Neither want violations

of habeas corpus and neither sanction torture. And I suspect

conservatives agree with liberals that government authority should not

extend to capital punishment. And I suspect conservatives agree with

liberals that government has no cause to care about gay marriage, no

cause to ban it.

The economic balance point between "uplift the individual American"

and government power is the area of disagreement. Both liberals and

conservatives agree that planned economies do not thrive. Are there

any cases where we might know how a government could usefully

intervene in the economy? Here people seem to disagree.

In the end I think I would agree with conservatives more if they were

as skeptical of private concentrations of wealth and power as they are

of governments.

Chris K,

This conservative is very skeptical of concentrations of wealth and power; indeed, I think most conservatives agree that the less influence that the wealthy or monied interests play in politics and government the better. The difference, however, is that we can always count on these players to act in their own economic self-interest, which is useful for a free economy and their very purpose. The government, however, is composed of individuals and parties that do not necessarily advance the most efficient, effective or even intelligent solution. While an individual politician can be counted on to act in his/her own self-interest, that unfortunately is not the purpose of government. They exist only to represent their constituency, not themselves.

It is for this reason that I distrust government more than private interests or the wealthy, but keep a watchful eye on all the players.

Post a Comment